Fusing Human and Robot Commands

Introduction

Machines are slowly transforming from devices we control to devices with which we cooperate to achieve a shared goal. To most people, this transformation is probably nowhere more apparent than in the automotive industry. With new advanced systems such as BMW’s driving assistant, humans are no longer the sole drivers of their cars. The issue now arises that given different steering commands between a human and an assistive system, it is unclear whom the car should follow. In some situations, the assistive system might prevent an accident, while in others it might misjudge the situation whereas the human reacts correctly.

Such a scenario in which multiple agents want to control the behavior of a system is often referred to as shared control. Behavior Circuits can be used for shared control applications by fusing the command of a human and assistive system based on rules. The advantage of behavior circuits compared to other approaches is that their rule-based structure makes it easier for the human to predict how the overall system will react to its commands.

Shared Control Example

In this example application, a scenario was set up in which a human teleoperated a mobile robot. The operator was in this case tasked with navigating from a start point to a specified target. To benefit from assistance the joystick was subject to random time delays, jittering, and a coarse discretization of the input. This was meant to simulate teleoperation under a laggy connection using bad equipment. The specifics can be seen in the source code.

To compensate for these impediments two types of assistive systems are used:

The first is an emergency collision avoidance system that turns and breaks if the system would otherwise collide with an obstacle.

The second assistive system, the steering assistance, tries to help the human steer to a specified target position by planning and following a path from its current position to the target.

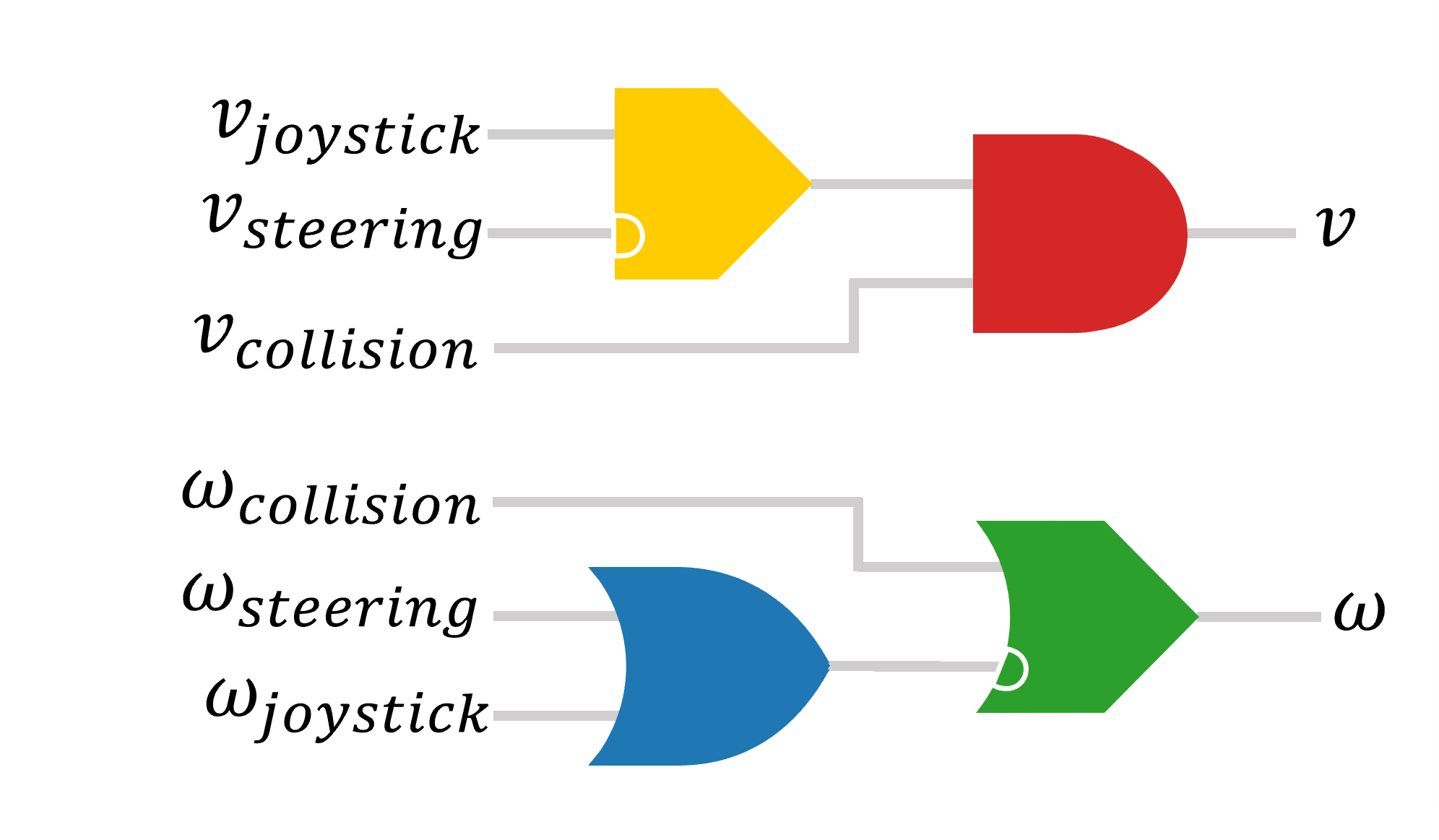

A sample circuit to combine these two agents can be seen here:

It is divided into two subcircuits controlling the angular velocity \(\omega\) and linear velocity \(v\).

It is divided into two subcircuits controlling the angular velocity \(\omega\) and linear velocity \(v\).

The sub-circuit for linear velocity implements the rule drive like the human OR the steering assistance if the human AND the collision avoidance system want to drive.

The sub-circuit for angular velocity implements the rule turn like the human OR the steering assistance EXCEPT IF the collision avoidance wants to turn, then turn like the collision avoidance.

These rules ensure that the system will not collide with an obstacle no matter what happens, while still allowing the steering assistance to support the human operator.

The full source code for this example can be found here along with instructions on how to run it.

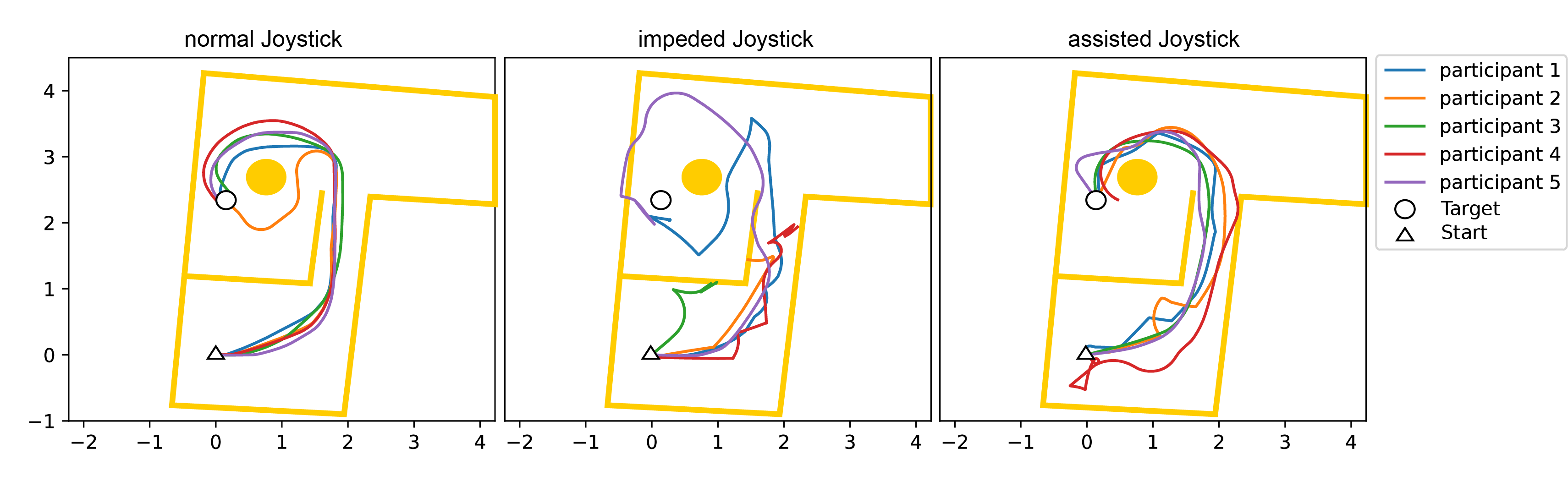

Results for a sample experiment with 5 participants can be found below.

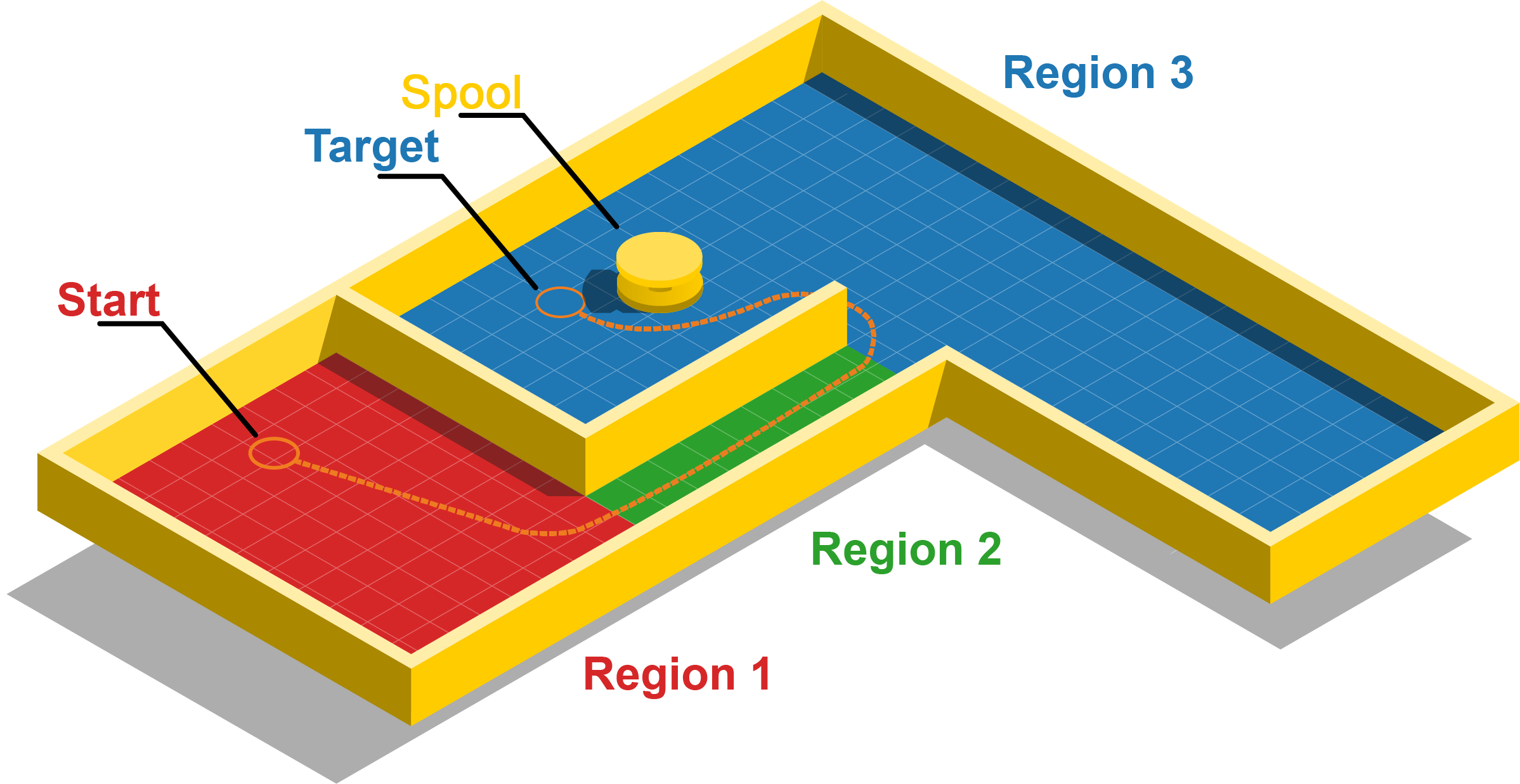

These experiments took place in a specially set up arena with different regions modeling different complications.

A turtlebot burger was used as a robot.

An overview of the arena as well as a photo of the robot in the arena can be seen down below:

The first region is a wide-open area with a small opening leading to the next region. While a steering assistant can help produce a smoother trajectory, a collision-avoidance system is not needed. The second region is a narrow corridor where it is easy for an impeded driver to collide with a wall. The third region features a huge spool at its center. Since the robot’s laser scanners only pick up the much smaller inner diameter of the spool, the spool models an obstacle that is only seen by the human.

The trajectories driven by each participant can be seen down below.

To compare the improvement over the impeded joystick a baseline with an unimpeded normal joystick was first performed.

As one can see using behavioral circuits to assist human drivers improves their driving performance significantly.

As one can see using behavioral circuits to assist human drivers improves their driving performance significantly.